by Lisa Morton

There must be a lot of snakes in Asia.

Obviously I’m no expert in herpetology, but I know Asian cinema, and I can testify to how many Chinese, Hong Kong, Japanese, and even Cambodian horror and fantasy movies focus on snakes. Or, more specifically: Spiritually advanced serpents that have taken human form. I guess you could call them were-snakes.

Many Asian countries have their own ancient folktales about transformed snakes, but none is more famous than “The Tale of the White Snake”. Considered to be one of the great fairy tales of Chinese literature, the story probably originated during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279 A.D.), and has been re-told in dozens of variants over the centuries. In its most classic form, it tells of White Lady, a snake who descends from the fairy realm and takes human form, accompanied by her maid Xiao Qing (sometimes referred to as “Green Snake”). White falls in love with a young man named Xu Xian, who runs an apothecary shop; they are married, and – with Green – move to Suzhou, where White’s renown as a healer soon spreads. They’re happy until a self-righteous monk, Fa Hai, arrives; Fa Hai eventually kidnaps Xu Xian, and the women are forced to fight him. He triumphs over White and buries her under the Leifong Pagoda, but Green polishes up her sword skills and eventually returns to free White, which she does after a massive three-day battle. In the end the monk crawls off to the bottom of a lake and is imprisoned in the shell of a crab, and it is believed that the inedible abdomen of the lake crab is what’s left of the vindictive and bitter Fa Hai.

In the earliest versions of “The Tale of the White Snake”, the monk is virtuous and is successful in imprisoning White Lady beneath the Leifong Pagoda (which was a real structure); however, over the centuries, the story’s sympathies shifted to the snake woman, and when the actual Pagoda collapsed in 1929, the tale was altered again to include the Pagoda’s fall as part of Green’s rescue of White. Scholar Wu Chao has also noted that “White Snake” is really a feminist tale which “reflects the aspiration of ancient Chinese women who struggled under the restraints of the feudal system to gain the right to build their own lives.”

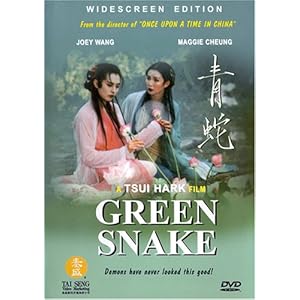

“The Tale of the White Snake” has been adapted to literally dozens of Chinese films, operas, and television series. The most famous adaptation is probably Tsui Hark’s 1993 GREEN SNAKE, starring the astonishing Maggie Cheung as Green and Joey Wong as White, with martial arts actor Vincent Zhao Wenzhuo as Fa Hai.

My adoration for GREEN SNAKE has already been discussed in earlier columns (to say nothing of my book THE CINEMA OF TSUI HARK), so another discussion of GREEN SNAKE is probably unnecessary at this point. Let’s just say the film hews fairly closely to the original story, but relies a great deal on sensuality, female empowerment and bonding, stunning visuals, a vibrant score, and of course the performances of two of Asian cinema’s best (and most beautiful) actresses.

Before Tsui’s masterful take on the story, though, there’d already been dozens of versions. I confess I haven’t seen the 1958 Japanese version THE TALE OF THE WHITE SERPENT (released internationally under the title PANDA AND THE MAGIC SERPENT), but it’s considered now to be the first color anime film. In Hong Kong, the Shaw Brothers alone made at least three different versions, beginning in 1956 with the Japanese collaboration THE TALE OF THE WHITE SERPENT, moving on to 1962 with the opera film MADAM WHITE SNAKE (starring legendary beauty Linda Lin Dai), and finally ending in 1976 with the incredibly strange THE SNAKE PRINCE, a lunatic mix of musical (the songs are full-on ‘70s disco, complete with wa-wa guitar and brass sections) and martial arts, with the genders from the original story bent to accommodate the star presence of Ti Lung, as the eponymous magical snake who descends to earth and falls in love with a human maiden. I wish I could recommend THE SNAKE PRINCE as a refreshing new telling of the old tale, but it really can only be considered a curiosity these days. With its goofy and stilted musical numbers, day-glo costumes, and comedic interludes, it’s not exactly in the Shaw Brothers top films.

Unfortunately, one of the most interesting spins on the story – 2000’s PHANTOM OF SNAKE – also ultimately doesn’t work. This low-budget Hong Kong production tried to put the snake women into a full-on horror story with a contemporary setting, centering on a Hong Kong detective (Jimmy Wong) trying to solve a series of mysterious murders. A chance encounter with a snake expert suggests the victims have all died of snake bite, and the detective eventually encounters the two snake women, played here with lots of glitter and writhing by Jade Leung and Cecelia Yip. There’s also some inexplicable business about how moonlight makes the girls go crazy (it’s never clear exactly what the moonlight does, except make them writhe about even MORE), and the snakes searching for a fossil snake egg that’s actually one of their husbands (HUH?). Unfortunately, the bizarre and confusing script isn’t helped along any by either Joe Hau Wing-Choi’s deadly dull direction or the two lead actresses’ performances – they seem to have taken Joey Wong and Maggie Cheung from GREEN SNAKE as their models, but have borrowed only the physicality of those two women, with their unique undulating walk and languid body movements, and not the intensity and sheer joy of Wong and Cheung. As with THE SNAKE PRINCE, PHANTOM OF SNAKE is best left to completists.

.front.jpg)

The oddest of the snake movies is probably the 2001 Cambodian production SNAKER. This one follows a Cambodian legend of a woman who becomes pregnant by a snake god, and gives birth to a child who grows up to be a beautiful woman with writhing snakes for hair (apparently SNAKER is famed in some circles for the way its director Fai Sam Ang achieved this effect: He really did attach a number of live snakes to a wig, which he forced the actress to wear). SNAKER has its moments – mainly some charming, fairy tale-like imagery – but overall its slender production values and barely-competent filmmaking are likely to leave most viewers feeling slithery in the worst way.

Japan hasn’t had quite the obsession with were-snakes that China and other mainland Asian countries have had, but it’s still made interesting use of snakes in cinema. Nobuo Nakagawa, often considered to be the godfather of modern J-horror, made 1968’s SNAKE WOMAN’S CURSE, which is really more of a ghost story but does toss in snakes for good measure (again, I confess I’ve yet to view this one, so we’ll save it for a future column).

And although it doesn’t include a single real snake, Shinya Tsukamoto’s 2002 A SNAKE OF JUNE is worth mentioning, mainly because anything by Tsukamoto (most well-known for his crazed industrial/punk classic TETSUO: THE IRON MAN) is worth talking about. Shot in a steely palette of intense blues and grays, A SNAKE OF JUNE delves into erotic horror by following Rinko, a repressed young woman who makes her living as a phone counselor for a suicide hotline. Rinko is trapped in a loveless marriage to Shigehiko, an older businessman whose obsession with perfection has him spending more time cleaning his kitchen sink than paying attention to his desperate young wife. Rinko receives a call one day from a man she’s counseled at work, a man who is now blackmailing her with illicit photos of Rinko’s one afternoon in which she entertained herself wearing a short skirt; the blackmailer forces Rinko to engage in humiliating acts in order to receive the negatives to the incriminating photos. The blackmailer (played by Tsukamoto) next kidnaps Shigehiko and forces him to wear a strange mask and witness a sexual act followed by a double murder. The blackmailer reveals that he’s dying of cancer, and forces Rinko to reveal a terrible secret of her own before she finally overcomes her repression in a spectacular climax (no pun intended). The title refers to June’s rainy season in Japan, when snakes are frequently driven up out of drainage holes and into the open – an apt metaphor for the shame, guilt, and self-loathing that Rinko and Shigehiko must try to rise above (there is, however, also a freaky scene in which a sort of mechanized snake that’s an extension of the blackmailer’s penis winds around Shigehiko – leave it to Tsukamoto to go for the classic Freudian thing). If A SNAKE OF JUNE lacks some of the frenzied kineticism and industrial fetishization of TETSUO, it also features carefully constructed layers of suspense and finely observed social commentary.

Later in 2011, we’ll be getting the latest version of White Snake, when A CHINESE GHOST STORY’s director Ching Siu-tung releases THE SORCERER AND THE WHITE SNAKE. Given Ching’s track record as a cinematic fantasist (in addition to A CHINESE GHOST STORY I, II and III, there’s also the magnificent and poignant TERRACOTTA WARRIOR and the brilliantly unhinged SWORDSMAN II and III), this promises to be one of the very best versions of the story (and the first presented in 3-D). The casting of Jet Li in the role of the monk Fa Hai doesn’t exactly hurt, either. Stay tuned…

--Lisa Morton