Monster Librarian

Hellnotes

Dark Scribe Magazine

Horror World

FearZone

Horror Fiction Review

Dread Central

Throughout the month of October, we'll all be posting various book reviews for your enjoyment.

Below are the first of The Black Glove's reviews for this annual project hosted by The Monster Librarian.

20th CENTURY GHOSTS

by Joe Hill

In the life of a reader, short story collections that gestalt so immediately, resonate so deeply, are a rarity. Joe Hill’s “20th Century Ghosts” is one of those exceptional books.

I haven’t been so moved by a chain of stories since my wonder years of discovering Ray Bradbury’s poetic prose. There were times that I had to place the book aside to examine my reaction to its latest offering. And that is the power of this man’s voice. He can be so subtle that his fears creep up on you and become your own fears; his emotions become your mirror.

Hill is steeped in the genre, to the extent of giving a knowing wink or two to the initiated (the scene in “Pop Art” with the dog and the station wagon, for instance), but never at the cost of pandering or posing. In fact most of the stories included in “20th Century Ghosts” transcend the genre in such a way as to break down the walls that, at times, hold horror too close to itself. He does not allow style to play first fiddle to the simple act of telling the story, as he displays a basic love for the tale and not the words. Yet they are heart wrenching, nonetheless. His prose has a buried richness that makes the words jump from the page.

And for the writers in the crowd, this may be some of the most impeccable editing I’ve seen in a long time. Every word matters in terms of the story--not the style.

The highpoints of the collection?

“Best New Horror”, the leadoff tale of a jaded horror anthology editor (I was thinking Stephen Jones the whole time) who finds the perfect story, and becomes obsessed with tracking down its mysterious author, only to find that all of those horror clichés he’s despised for so many years have come around to bite him in the arse.

“Pop Art”, an absurdest piece about a balloon boy befriended by a flesh and blood underdog. It’s a tearjerker from start to finish and I have so rarely been so glad to have my emotions manipulated.

“Abraham’s Boys” is a truly disturbing take on the Van Helsing/Dracula mythos that examines the dissolution of father and sons.

“Voluntary Committal” will stick with me for years. Enough said.

“You Will Hear the Locust Sing” is one of the subtlest post-Columbine stories I’ve ever read. When the violence comes, it’s shocking and numbing at the same time.

“My Father’s Mask” is haunting and chilling in its unspoken perversity and terror. I defy anyone to read it and not get a chill as the final paragraph unfolds.

I’ll stop there. Although I could hit on every story, I think it best to read them for yourselves and live inside this man’s world of words. I will add that every story is about some relationship- good or bad- that illuminates how we interact with those who we love and love us. There is nothing simple about this book, and anyone who comes to it for easy entertainment will walk away with more than he/she bargained for.

One last note: Christopher Golden’s introduction may be one of the most accurate introductions I’ve read in years for an author’s short story collection (much like John D. MacDonald’s introduction for King’s first short story collection), in terms of awe and respect for Hill’s work. I imagine he was much like myself after having read “20th Century Ghosts”- in a daze and examining my own words for this transient beauty. I am in awe. And that is a rare thing these days in this genre.

--Nickolas Cook

WORLD OF HURT

by Brian Hodge

Brian Hodge’s work should come with a warning label: WILL MESS WITH YOUR PRECONCIEVED NOTIONS OF FAITH AND GOD.

WORLD OF HURT is the story of Andrei, a young man who comes back from death’s door with some very disturbing memories of what lies beyond the threshold of flesh. It’s a story of redemption, betrayal, and sacrifice, of blood and flesh, and spirit and soul. The tale alone is enough to keep his readers up at night, but Hodge also opens a dialogue with his readers, in essence asking, ‘What do you really believe happens after we die?’ and more importantly, ‘Why?’ His revelation of why God can seem so cruel will leave many conservative religious folks reeling in horror, as he contends that the white light at the end of the tunnel is a lie, and only horrors and darkness await us, and that there is no God, but a being called Ialdabaoth waiting to suck us back into It’s terrible, cold essence of despair.

In WORLD OF HURT, Hodge creates a mythos every bit as dismal and bleak as Lovecraft’s Elder Gods, and in fact, Ialdabaoth comes off as a distant cousin to these alien dissenters of mankind. But it’s the peripheral characters with which he’s concerned, the saviors and killers, of this mythos, not the Gods beyond. It’s their emotions and struggles that keep the pages moving along. There is no cold Lovecraftian phrasing here, but pages suffused with warmth and genuine awe for the human spirit, as Hodge handles his characters with a respect and emotion that we’ve come to expect from one of our great under appreciated masters of the craft. He even finds a way to make the antagonist seem pitiful, despite the bloody cruelty of his work.

WORLD OF HURT thrusts you, sometimes unwillingly, into the mind of a remorseless killer, a timeless assassin of killers, and a troubled and confused young man who cannot find rest from his memories of what awaits beyond the shadowy veil. The pace is quick, the writing crisp and smart, the underlying themes and philosophy thought provoking. In short, this is the kind of smart horror that’s missing from the chain store shelves these days. Thank God, for Earthling Publications for brining Hodge’s excellent voice back to the reading public. It’s intelligent, emotive work that only gets better as time goes on. (For those of you who doubt, also pick up WILD HORSES, one hell of a great read from the first page.)

This is a loosely connected work to a trio of shorts published over the years, “The Alchemy of the Throat”, which originally appeared in LOVE IN VEIN (edited by Poppy Z. Brite), “The Dripping of Sundered Wineskins”, which appeared in the sequel anthology, LOVE IN VEIN II: TWICE BITTEN (also edited by Poppy Z. Brite), and “When the Bough Doesn’t Break”, which appeared in the DAMNED anthology (edited by Dave Barnett). But WORLD OF HURT definitely redefines the territory he explored in these previous works. And as he mentions in his Afterword, it’s territory he will undoubtedly dip into again. It should be a rich mine of wonders for a man who can weave dark conspiracies from the world’s bloody history.

--Nickolas Cook

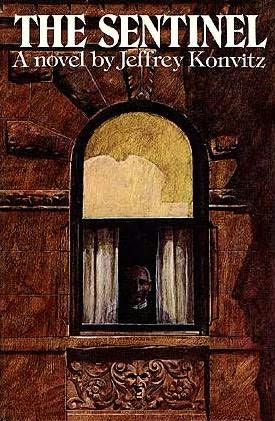

THE SENTINEL

By Jeffrey Konvitz

My suspicion is that there was a different expectation from horror in the 1970s. “The Sentinel” is not as horrific as one might expect from, what is considered, a classic horror work from the early boom of the genre. In 1974, Ira Levin and William Peter Blatty were the leaders of the burgeoning genre, and King had yet to become a household name. Most people didn’t know the difference between a well-written thriller vs. a balls-to-the-wall horror tale. One part mystery and one part horror, this is the space in which Konvitz’s novel falls.

When New York City fashion model, Allison Parker, decides to rent an apartment in a crumbling brownstone building, she is pulled into the mystery of the domicile. A blind priest sits at his eternal vigil in the top floor, and the rooms are full of people who seemingly do not exist. Her life is going out of control after the death of her father; her boyfriend quite possibly murdered his wife to be with her, and who is the naked old man that walks the floors above her at midnight?

Universal Studios took this story and turned it into a classic creepy film. The movie is full of nice touches of light and shadow, slow buildups to some great scares, and great characters we care about.

The book has almost none of these things.

What it does have is a nasty take on lesbians (referred to by most of the characters as perverts), shite dialogue that sounds like a Saturday afternoon radio drama from the 40s, and block-headed descriptive passages that gloss over any attempt at elegance. The extraneous scenes that could have been weeded from this work are too many to count here, but let us just say that a good editor would have been a godsend. And what’s truly astounding is that Dario Argento took a fairly similar notion and created the film “Susperia” a few years later.

Go figure.

All that aside, why is this considered a classic of the genre?

Because in some ways this is a transitional work, one that we can look back on now and recognize as a link between gothic horror and modern (urban) horror. Konvitz took one of the most identifiable tropes of gothic horror (lone female moves into place with mysterious past) and used it to create an admixture of old and new. The story strives for a modern cosmopolitanism, while sitting firmly in the tradition of gothic literature. Sadly, it doesn’t always work, but “The Sentinel” still remains a brick in the wall of the genre.

--Nickolas Cook

THE SPEAR

by James Herbert

When Herbert is on, he’s one of the best horror writers in the world. And I’m not just saying that. For anyone who’s ever read “The Rats”, “The Fog”, or “The Dark” can tell you he writes splatter horror like no one else in the business. But he has been known to write a quieter horror as well, as evidenced by such books as “The Magic Cottage” and “Fluke”. “The Spear” falls into that quieter category, as he tells the story of Harry Steadman, ex agent for Mossad living in London and working as a private investigator. When he’s asked to find a missing Mossad agent for his old spy fraternity, he refuses, tired of the violence of his old life. But his partner is tortured and killed at his front step and he makes it his business to find and destroy the people responsible. What he doesn’t bargain for is the desperate depths that his old Nazi enemies have sunk to regain world power.

“The Spear” plays more as a spy novel than a horror novel, and with that caveat having been said, fear not...there are moments of horror. For Herbert has attempted one of the few true mummy novels in horror. There are only a few of them around, and most were written long before this one. He does an admirable job of working the Nazi angle into his tale, and if nothing else “The Spear” makes for one heck of a rousing action story. But the horror isn’t going to come as a surprise to anyone who’s actually reading the book. There are plenty of hints of what’s to come, as we learn how Heinrich Himmler never actually died and the body identified as his was only someone pretending to be him to save the last power circle of Nazi masters from the righteous fury of the conquering armies. There is a certain surprising conservative message between the lines, as hedonistic sex and a hermaphrodite are made the targets of some pretty vile remarks, something I would never have seen coming from Herbert, who may be one of England’s most subversive living authors. But as this was written in the early 80s, things do change, so perhaps his philosophy has as well.

There is also a nice subplot about Hitler and his love for Wagner’s works, and a pseudo-religious one about the spear used to stab Jesus Christ as a weapon of mass evil destruction. But in the end, as much as the story seemed to rely on these dual components, neither of them carry through to the end as much as the spy angle, or the Himmler angle.

Herbert’s use of the solitary hero strongman was also used in another excellent horror novel, much like “The Spear” in its quiet insinuations instead of full blown blood and guts extremes: “Sepulcher”. And if you find “The Spear” to your liking, then I would suggest finding a copy of this one as well.

--Nickolas Cook