THE HARROWING

Alexandra Sokoloff

St. Martins

$6.99 MMPB

So many times it’s tough to read a great horror novel and know it’ll never translate to the screen. Sure, we don’t always get to see our favorites become blockbuster films, and most modern horror movies are homogenous, at best. But there are some novels that just scream to become movies. If any new horror novel deserves to garner a larger audience via the big screen treatment, it’s Alexandra Sokoloff’s 2006 novel, THE HARROWING.

Sokoloff is a well known Hollywood screenwriter, so it hardly comes as a surprise that her page fiction feels so cinematic. Using archetypical characters- the jock, the brain, the misunderstood slut, the rebel, and the poor little Goth girl- that feel as if they’ve stepped from a John Hughes movie, she gives them new life throughout the narrative, while creating a fast paced and creepy story.

Venerable Baird College is deserted for the holidays, except for five dysfunctional students who manage to find each other in the darkened halls. During a stormy winter night together, they decide to have a few laughs with an Ouija board. Unfortunately they come in contact with an ancient entity that’s been waiting for someone to open the doorway to our world. What begins with simple planchette communication, soon becomes feats of telekinesis and telepathy. What starts with seduction of the unknown, soon turns into a deadly obsession for all of them.

The scares are well placed, jolting the reader with cinematic jump scares during the quiet moments. In lesser hands this would be a cheap trick. But talented and wily Sokoloff knows her readers are probably consummate horror pop culturists, so she makes sure to throw in a few unexpected twists and turns that are sure to leave any reader, connoisseur or novice, breathless. Sokoloff knows her horror history, both in film and book, so it’s no surprise to find her paying homage to both THE HAUNTING and LEGEND OF HELL HOUSE, two classics of the genre.

When you add all this up, it’s simple to see why she’s definitely my pick for the future of big house horror.

THE HARROWING is a horror read that’s guaranteed to keep you up all night to get to the explosive finale. It leaves me eager to see more from this dark new voice in the genre.

Author’s web site

--Nickolas Cook

Martyrs and Monsters by Robert Dunbar

Dark Hart Press

Trade/$17.99

Robert Dunbar is best known for that neo-classic of the late 80s, THE PINES (Leisure), so when he announced its sequel THE SHORE (Leisure) his fans were justifiably excited. With it, he once again proved he is the master of the quiet horror novel.

Now he returns to the horror fold with a superior collection of short stories in MARTYRS AND MONSTERS, proving he also knows how to craft short stories that are as effective as his longer narratives.

There is an old world sense to his writing that few modern horror writers can match- a carefully cadenced phrasing makes the difference in how the story unfolds. It’s imbued with a trademark Southern Gothic sensibility that most genre authors are unable to capture. His editing is clean, razored down, for maximum pacing and stylistic impact and plays a large part in how well his storytelling works. MARTYRS AND MONSTERS is filled with hauntingly sensual imagery that touches a primordial fear center not unlike King.

And this is not the first time (and one can guess, not the last time) Dunbar has been compared favorably to King, even to Koontz. And this collection clinches it. He deserves not only the critical comparisons, but also the success his two more well known peers have enjoyed. Every story hooks the reader, pulling him along some rather unsavory paths and realities, spiced with a creeping sense of the dark come home to roost.

One of the best qualities about Dunbar’s work (and one that most critics and readers pick up on right away) is that he does not hold with the modern day penchant for torture porn aesthetic and gore described in clinical detail. His violence is implied- forcefully- and tends to disturb on an emotional level that is far more effective than the transient visceral ‘gross out’ scenes we see too much of in what is termed ‘modern’ horror. It haunts more than disgusts, and sticks like cold blood to your soul.

Dunbar’s cast of characters come from the disenfranchised populace- minorities and criminals (sometimes both)- struggling to survive in a cold world that has cast them aside because they do not fit. And that is what horror does best: speak for the lost souls of the world. But through his misfit cast he does not strive to denounce the injustice of the universe. Instead, as he does so well in ‘High Rise’, he attempts to find a heroic sense of acceptance of that injustice and its vagaries, the universe’s unfeeling machine like quality that digest all equally. Just because the hero doesn’t always live, doesn’t make him a loser in this game.

Each story is memorably, but a few that will stick with this reviewer for a long time to come (as do the old masters’ stories) are:

‘Mal de Mer’ is disturbing, as if Edith Wharton’s supernatural fiction met Lovecraft, creating an unnerving erotic pleasure, maybe one of the best of its kind, and certainly one that deserves nomination for a Stoker.

With ‘The Folly’ Dunbar once again provokes Faulkner’s ghost to tell the clever tale of a debauched Southern family (all named for Greek mythical personalities) who discover their own ‘Jersey Devil’ creature living in their swamp. One gets the sense that the author is poking fun at the industry wide perpetuation (a mistaken one, by the way) of his ‘one hit’ success with THE PINES and he does so with tongue in cheek.

‘Explanations’ is one for the horror fanboys gone wrong, with a ‘sharp’ punch line. If you’ve ever been to a fanboy convention, then you’ve no doubt seen hundreds of Jimmys and Wagners plodding from table to table to gush at aging actors whom they cannot differentiate from their characters. And if you’ve ever wondered what these socially challenged folks live like in the ‘real’ world it ain’t pretty…and it smells funky, too!

‘Killing Billie’s Boys’ is a deceptively intense story of urban black magic and betrayal that plays a razor edge of eroticism against our expectations and leaves the reader feeling dirty and excited.

With ‘Gray Soil’ and ‘Red Soil’ he tackles the ever popular zombie sub-genre and makes it his own.

It’s safe to say that Robert Dunbar can write anything to which he sets his mind. We are lucky to have such a wordsmith in our midst. Collections like MARTYRS AND MONSTERS don’t come along often (buy it now, while you still can, before it becomes an outrageously expensive collector’s item). And writers like Robert Dunbar don’t materialize in the writing community everyday- certainly not in the horror community. Let us give thanks for his continued attempts to bring professionalism and craft back to an ailing genre, and hope he is more widely published in the future.

--Nickolas Cook

THE SUMMER I DIED by Ryan C. Thomas

Coscom Entertainment (2nd edition)

Trade/$14.99

Back when I first reviewed Ryan Thomas’ THE SUMMER I DIED, there was an extreme sub-genre, known by enthusiasts as ‘backwoods’ horror, which is an offshoot of the same sub-genre in film: movies like DELIVERANCE, STRAW DOGS, WRONG TURN, and the ultimate in backwoods terror, TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE. In the horror literature world it comprised of some pretty gruesome titles by the likes of Joe Lansdale, Jack Ketchum, Ed Lee, Richard Laymon and Weston Oches. Now it’s a thriving sub-genre, with more movies and more books than I can name here available. So what better time for Coscom Entertainment to release this new, cleaned up edition of Thomas’ debut work?

THE SUMMER I DIED is an unrelenting read.

Grisly.

Bloody.

And, unfortunately, quite plausible.

Author Ryan C. Thomas tells the story of Roger and his childhood friend, Tooth, and what happens to them in the backwoods of a small New Hampshire town, when they run across a dilapidated cabin and find it’s the terror dome of a sadistic (and very imaginative) killer.

But the author doesn’t throw the reader into the horror before some careful consideration for his main characters. Thomas takes the time to paint a pair of likable guys, and give them a sense of humor and life before tossing them to the lions. Roger, the industrious one, and Tooth, the slacker of the duo, are young men that anyone might recognize as the guys next door, unhappy with life in a small town, but hopeful for a change. And that’s what makes this novel so damned hard to get through without feeling sick and dirty. Thomas holds nothing back; he describes all the gore, all the pain, and all of the terror blow-by-blow. THE SUMMER I DIED is written in first person, so there should have been no suspense about Roger’s survival of the ordeal. But several times I had to remind myself that he lives through it, or else no one would be telling the story, right? It’s been a long time since I had to do that for a first person narrative. That’s the power of good descriptive writing, and building a dense atmosphere of palpable horror for the reader.

The obvious caveat is that this style of writing may not be for everyone. Some may see THE SUMMER I DIED as violence for violence’s sake, a literary equivalent to a Friday the 13th film.

But what makes it work so well is the characters’ sense of humanity. Even at his worst, the killer, named Skinnyman in Roger’s narrative memory, gains our sympathy even as he utterly devastates the human body, and does such outrageous things to a woman’s severed head that I can’t even bring myself to print it here. His methods are extreme…maybe too extreme for some readers, so be warned now. Even the dog, Butch, has a sense of humanity, and becomes like another character for the story.

In this second edition, the rough first few pages have been smoothed out for a better pace and phrasing. The flashbacks don’t feel quite as intrusive as in the 1st edition. The spotty dialogue that peppered the original print has also been cleaned up a bit and moves more seamlessly through the narrative.

Since his debut release, Thomas has been busy editing a fantastically original anthology for Permuted Press, called MONSTROUS (http://www.permutedpress.com/) and doing what writers do best: write what he knows and feels, and just plain making it better with every new sitting.

And what I said before, still stands true with this 2nd edition of THE SUMMER I DIED: He still has a good grasp of theme and characterization; his dialogues scintillate off the page. And I still charge that Thomas may very well be the next big name in extreme horror. For those fans of extreme horror, and ‘backwoods’ horror, or both, I recommend THE SUMMER I DIED, 2nd edition from Coscom Entertainement

--Nickolas Cook

Necropolis

By John Urbancik

Bad Moon Books

Limited Perfect Bound Trade/$17.95

Some readers may find John Urbancik’s newest release from Bad Moon Books, NECROPOLIS, to be a diffuse and surreal nightmare, brought to life through poetic phrasing and images. But if close attention is paid, its pages will also reveal an erudite and literate homage to Poe, the master of the macabre. The careful reader will pick out Poe’s titles and phrases scattered throughout the narrative.

When five people find themselves trapped in an ancient ‘city of the dead’ after dark, they encounter strange beings- including Nyx, the Greek primordial goddess of the night- lurking within the vast cemetery’s benighted stones and crawling vines, and must make life and death decisions that seal their fates.

Besides the above mentioned Poe love, the lynchpin to this short tale is Urbancik’s lyrical style of writing; some passages could even be considered musically when read them aloud. No one can dispute his ability to make a sentence stand attention. That, coupled with his cemetery photos, truly helps create a sense of ominous mythology in NECROPOLIS. In fact, it reads as if he intends his cemetery setting to be an existential playground through which his characters must traverse.

That being said, there are issues that may leave some readers…well, feeling a little dead inside about NECROPOLIS.

For one, his characters suffer because of the brevity of space allowed to unfold the story: they feel vague and underdeveloped. One wishes he’d been able to create a bit more empathy for Kevin, Jill, Kelli, Anna and Darren. Unfortunately none exists.

And that fact doesn’t much help the narrative, which in itself already suffers from too much twining. The whole reads in a very disjointed manner, which may have been Urbancik’s intention, and admittedly may be only a matter of personal taste. Unfortunately I found myself having to go back to re-read passages to make sure I was still with one or other of the characters. This abstract quality may risk alienating some readers by its obscurity.

So is NECROPOLIS worth the cover price?

Undoubtedly.

Even if it were only for Urbancik’s excellent photos alone.

But it is also recommended because, despite the diffuse, and sometimes confusing, nature of the narrative, it is a well written story, with some real touches of Gothic beauty. Urbancik is a time tested craftsman that can always give his readers an interesting story, if not always told in the traditional manner.

John Urbancik’s web site:

--Nickolas Cook

TIME CAPSULES by Bill Lindblad

The Dead by Mark E. Rogers

Every reader has a book or two with which they form a deep association. Sometimes it's because the book was with them during a key event in their lives, and sometimes because the story resonates on a deeply personal level. One of those books, for me, is The Dead.

I first discovered this book in a small used bookstore in Hampton Roads, Virginia. I purchased it primarily on the strength of the author's name: Mark E. Rogers had written some entertaining (and beautifully illustrated) humor books featuring the Samurai Cat character, and two remarkably horrific and brutal "mainstream" fantasy novels (Zorachus and The Nightmare of God) chronicling the fall of a missionary in a city of dark sorcery. The books had shown imagination, a familiarity with traditional structure (the pair formed, at their core, a classic tragedy) and an ability to tailor his language to the story he was telling. I was curious to see what he could do when he turned his attentions to horror without the heroic fantasy edge.

I was in the Navy at the time. I was on chapter four when I set the book down to attend to personal matters. When I returned about ten minutes later, someone had stolen the book.

Just under ten years later, I found another copy in a used bookstore in Richardson, Texas. During that time I had visited dozens of other used bookstores an aggregate of hundreds of times. I had braced the author for a copy at a convention, only to discover that he was out of copies and retained just the manuscript.

This is one of the books I've found most difficult to locate. Thankfully, the internet has made it easier to find these days. Thankfully, because the book is worth the hunt.

The Dead reads like a Catholic version of Left Behind by way of Keene's The Rising. Early into the book, everyone on Earth shares a dream of judgment. Most are found wanting; those who are not disappear. At first, people investigate the odd disappearances; very quickly, however, something more pressing takes center stage: the dead are rising from their graves, and every one of them is a rampaging body of rage.

The novel focuses on a small group of survivors, watching as the sun starts to dim and all complex devices break down. It alternates between action and discussion, and contrary to most zombie books the book excels during the discussions. Because of the atypical construction of the book, topics are not merely focused on survival and the relative value thereof but of the nature of theological belief and redemption. Most of the action sequences are strong, and there are many scenes of visceral horror although the author tends not to linger on graphic depictions of individual instances of violence.

If this is sounding like a wholehearted endorsement, it shouldn't. There are flaws within this book. Many flaws. Some are simple logistics (every truly "good" person on Earth disappears, and none of them happened to be in the presence of a wakeful person at that time?) Some occur when the author tries to step away from the local story of the group and reveal what's going on with the rest of the world, because it drastically shifts the momentum and pacing of the story. One is physical: it seems that only one person among all the survivors is capable of fending off the dead for any length of time, and the book threatens to devolve into a cross between a Men's Adventure book and a Bruce Campbell film at those times. And one is a deep and significant flaw in characterization: one of the two primary characters is repeatedly influenced far more by an old school cohort whom he hasn't seen in years than by his wife of a decade to whom he is generally portrayed as devoted.

Despite the flaws, however, the reader is treated to a remarkably well-considered attempt to integrate the Biblical end of the world into a story, and along the way encounters a "fast zombie" story that predates 28 Days Later by more than a decade. And if you're a lapsed Catholic, it's probably going to disturb you more than anything since the Exorcist... and probably more than that classic work. For those reasons, and because it's energizing to read horror novels that aspire to a deeper meaning even when they don't fully succeed, I can recommend purchasing this book if you find a copy that's not out of your price range.

Four stars out of five.

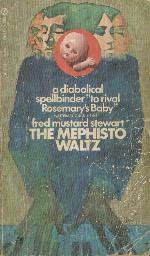

The Mephisto Waltz

In some books, nothing happens. In this book, nothing happens... but with style.

If you've already seen the movie starring Alan Alda, I pity you. If you haven't, please read Jen Orosel's take on the film, available in this issue, for an expert's view on movie. I'm going to focus on the book.

The book is written from the point of view of the wife of a failed pianist-turned-author. As with many novels from decades past (the novel was published in 1969) the book is short; the page count ends just short of 200. Of those pages, at least a quarter involve the main character waffling between contrary opinions. Paula metronomes between active and passive distrust of others, pitting their seemingly irrational behavior against the possibility of her own paranoia. Through her mind we get an excellent view of self-doubt, and she is a very sympathetic character; she is not prone to abandon her doubts when given convenient excuses to do so but she is relieved to have them proven baseless.

Of course, because of the nature of the story, those doubts aren't baseless. That much is revealed in even a cursory glance at the cover, and therein lies one of the problematic aspects of the novel: it's trying to do two things at once, and while the two are not fundamentally incompatible they tend to be so within the context of this book. The author is engaging the readership in a game of mental insecurity, where a character may be encountering an odd event or where the activities may be all in the character's mind; simultaneously, he provides enough details in other scenes to let the reader know which scenario is true. It's a psychological horror novel by way of Columbo.

The action in the book can be summarized by four or five scenes. The remainder of the book consists of people talking about issues related to the characters... the success of the retail store, Myles' piano practice, the possibility of an extramarital affair... and while these might otherwise be dull, Mr. Stewart uses these conversations (and internal monologues) to craft tension. This, in particular, leads to the horrible mangling of the story in film: the movie version works to include every key scene without bothering to create any tension, likeable or sympathetic characters, or to show the devastating impact of some events.

His word choice is excellent. In many instances, the insertion of a single word or phrase alters the reader's impression of the situation. Twice during the book I paused to appreciate this skill of the author. I believe it was notable primarily because of a significant related failing of the book.

In movies, product placement has become a part of the business. A company will pay a studio to include its brand name in billboards during a driving scene, or to have the actors filmed drinking a specific soft drink. This novel might have inspired such activity. Whether it's TarGard cigarette holders to minimize tar inhalation, Clorets mints, or Shalimar perfume, if there's a brand name, Stewart will mention it. Those three examples aren't chosen at random; they're all found within the initial four pages of the book. The novel is littered with other examples. The bad side of that is that it throws a reader out of the story, particularly when confronted by products which no longer exist or whose popularity has flagged; the good side is that it encourages the reader to focus on the craftsmanship of the word choice, which is otherwise (as previously noted) a pleasure.

I found the novel entertaining, with a conclusion and denouement which simultaneously disturbed me and provoked thought... two goals which may well have been precisely the intent of the writer. I was left liking the novel, but disliking the implications of the novel.

Four stars out of five.

--Bill Lindblad

THE CORMARANT by Stephen Gregory

A haunting is an interpersonal experience, and the haunted almost always has some past connection with the haunter. Stephen Gregory’s overlooked classic ghost tale, “The Cormorant”, is no exception to the genre rule.

When a deceased uncle wills a young couple his rustic beachside cottage they discover that the unexpected gift bears with it an odd attachment. They must become caretakers to a caustic cormorant (a large English coast bird). But what else have they inherited?

Gregory builds the story’s creeping doom in slow waves of insinuation, so the reader is never sure whether the husband (narrator of the tale) is actually haunted by his solitary uncle’s ghost or if he’s only imagining it as his orderly life is slowly disintegrated by the presence of the hated bird.

The author works best in metaphor, using the various aviary life that surrounds the couple’s new domicile to illustrate the husband’s growing dissatisfaction with his orderly life, his marriage, and even going so far at one point to use a lone outcast swan as a stand-in for the narrator’s frustrations. We feel his shucking off of accepted social morays and order as he comes to identify more and more with the acerbic titular beast, a bird that squirts shit, and uses its beak to stab at anyone foolish enough to get within range. There is a strong antisocial message. As the bird becomes the solitary hunter, diving the sea depths to retrieve its fishy livelihood, it becomes a feared and respected master of the local aviary society—much as the narrator strives to become.

The child, Harry, becomes the focal point for tragedy, as Gregory foreshadows the inevitable in squirming scenes of flame and folly. But these moments of foreboding do not detract from the last scene, a gut wrenching moment of realization that death is always near.

But this is also a story about an aging husband and father seeking his own identity in a world of classifications and nine-to-five until you die rational. And Gregory’s sympathetic heft pulls the reader into the narrator’s sense of lost purpose.

The author’s generous use of the language makes this a sure classic of the genre. His descriptive passages are excellently rendered, and his cormorant characterizations tug the story to the level of classical literature. The prose is tight, almost dreamlike in parts, as the dissolution of order takes place, and we are swept up in the bleak seashore community in these moments of dark beauty.

There are few ghost tales that work on so many levels as Gregory’s “The Cormorant”.

--Nickolas Cook

GHOST STORY

by Peter Straub

'The Time has Come to Tell the Tale...'

"What's the worst thing you've ever done?"

"I won't tell you that, but I'll tell you the worst thing that ever happened to me...the most dreadful thing..."

So begins Peter Straub's landmark horror novel Ghost Story; with the telling of tales...

Ghost Story's showstopper is the legend of Eva Galli. Half a century previously, five friends were implicated in the death of a young woman with whom they had all been in love. In grief-stricken panic, they hid Eva's body, and their shameful secret, away, supposedly forever. In doing so, they avoided ruinous scandal. In time, the killers lessen the malignant power of their nightmares by meeting, with solemn ceremony, as 'The Chowder Society', a club of sorts dedicated to the telling of horror stories. Straub has his character Don Wanderley (note that inverted 'M'; perhaps a discreet homage to Manderley, the home of that magisterial ghost, Du Maurier's Rebecca?) read about Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter in DH Lawrence's extraordinary Studies in Classic American Literature. So we see the relation between the Society's shared past and their cowardly attempts to, at once, disavow and disarm it:

'(They) hug their sin in secret, and gloat over it, and try to understand.'

But Eva Galli was not dead, indeed, she was not even mortal, in human terms; a shapeshifter, a manitou, an archetype of depthless evil, taking her pleasure in the corruption of innocence, she had turned the naive young men into murderers; now she would return, in differing guises, to haunt them unto death.

Surely a story to end them all. Yet this is just a continuation of a timeless tale - in fact, Ghost Story relates the evolution of storytelling. From the oral tradition of the Indians' encounters with Eva-as-manitou and The Chowder Society's civilised 'camp fire' tales; to the author's nods to those masters of American fiction Hawthorne and James; to Don Wanderley's would-be novel; to Ghost Story's fascination with the movies; to this discussion taking place on that most modern form of communication, the internet. Straub's book is the story of Stories. The beautiful but truly alien fiend known as Eva Galli tells her former admirers:

'I have lived since the times when your continent was lighted only by small fires in the forest, since Americans dressed in hides and feathers...We chose to live in your dreams and imaginations because only there are you interesting.'

An awe-inspiring thought for certain, but is Straub (as Eva) making a claim for the genuine existence of those creatures we dare not believe in? Or is he perhaps giving a voice to that most beloved of human inventions - the creatures we call Fictional Characters; do they not live in our dreams and imaginations? They are certainly alive and running riot, beyond the various storytellers' control, in the sleepy town of Milburn: Don Wanderley's novel-within-a-novel impinges on reality - a fictional reality created by Peter Straub – and characters see themselves in real-life movies playing in Milburn's cinema. In fact, and in fiction, Ghost Story's characters are given life, power, by the stories told about them, just as we turn typed characters on a page into creatures human and otherwise with our imaginations; only there are we interesting...

Some thoughts on the timeless charm of Eva Galli. Yes, she is the vengeful femme fatale men cannot resist...writing about. And yes, she is beautiful (of course she is - she is the creation of men, by way of Hollywood, the Dream Factory). But her beauty is almost irrelevant, for her face is blank, lifeless, and as Straub repeatedly makes clear, her true face only reflects ours; she is the cipher of Gustave Moreau's Helen at the Scaean Gate.

In the course of the novel, Eva has been a myth, a film star, a fictional character (as 'Rachel Varney' in Wanderley's first book) and a 'real-life' person; but she can only be those things because of us, because of the imagination she finds so fascinating. In the chapter titled 'Edward's Tapes' an old recording of her voice taunts a captive audience (Don's uncle had been taping Eva's fictionalised life story - another piece of oral storytelling for the benefit of posterity):

'Could you defeat a dream, a poem?' But to do so would be absurd; dreams and poetry have no meaning - no independent value - beyond our interpretation, beyond the meaning our imagination bestows upon them. Eva is essentially powerless, despite her boasts, despite her preening - we, the dreamers, allow Eva and her kind to haunt us. She, and we, revel in what the philosopher Michel Foucault termed 'the marvellous play of the imagination'.

Ricky Hawthorne, the lone survivor of the infamous five at the novel's end, (and notably, perhaps the only male character who truly respects women) tellingly compares Eva to Louise Brooks, the nonchalant, destructive Lulu of GW Pabst's film Pandora's Box, another allusion to the movies' seductive blurring of fact and fantasy, myth and reality; and of course, the endless, ever-changing power of Story. Near the novel's end, master storyteller Peter Straub for once gives it to us straight, and tells the truth about our need to hide our reality in the guise of tale-telling:

'What was the worst thing? Not the act, but the ideas about the act: the garish film unreeling through your head...'

Ghost Story was reviewed by Steve Jensen