Sunday, September 4, 2011

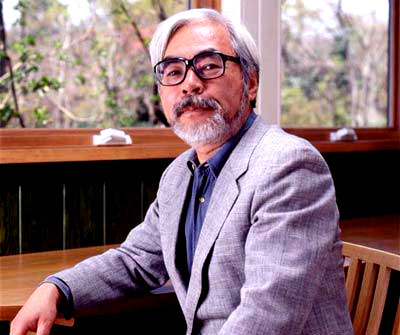

THE EAST IS RED #23: Hayao Miyazaki

Here’s how big a Miyazaki geek I am: A few years ago, when SPIRITED AWAY was about to open in the U.S., I found out that Miyazaki would be in L.A. for one press conference…in a few hours. I immediately got on the phone and pestered a friend who had Disney connections until he figured out a way to get me into the conference. I ditched work, I pretended to be a journalist, I sat in the El Capitan theater with 20 real reporters and critics and just basked in the knowledge that I was thirty feet away from genius.

Hayao Miyazaki is one of the world’s great filmmakers. And no, I didn’t forget to include the word “animated” in that sentence, because I rank him with Lynch, Scorsese, Fincher, Tsui, Kim Ji-woon, and any other great live-action director you might mention. Miyazaki’s skill in telling stories visually is unsurpassed; his personal obsessions are consistent from film to film, and yet always seem uniquely rendered. And I believe he’s alone in world cinema in being a filmmaker who has made a substantial number of feature films (ten to date as director) and has never made one that wasn’t superb. I’d argue that he has given us at least two full-on masterpieces, perhaps more.

The above-mentioned SPIRITED AWAY is one of those two, and is possibly the closest to a dark fantasy that Miyazaki has come (although the science fiction-themed NAUSICAA, with its vision of an ecologically-devastated earth roamed by giant mutant animals, is probably more genuinely disturbing). It also provides a fine example of why Miyazaki is a brilliant filmmaker. Look at the beginning: Chihiro is a pre-pubescent girl who is pouting in the back seat of her car as her father drives them to a new home. Dad gets lost along the way, and they wind up facing a strange, dark tunnel. Curious about where it leads, Dad parks the car and the family steps out to investigate. Miyazaki goes for textbook-perfect shots – low angles up on Dad, emphasizing his size and confidence, high angles down on Chihiro, who looks around nervously, and tracking shots moving through light into darkness and back again. But Miyazaki isn’t just going by the letter here; he’s also setting up the film’s mythology with firm, brief strokes. The first twenty minutes of SPIRITED AWAY speaks to the subconscious on some level that most filmmakers can only begin to touch; Miyazaki instinctively understands the universal meaning of tunnels, of bridges, of dusk, of abandoned buildings, of whistling wind and half-glimpsed shadows. On the other side of the tunnel Chihiro and her parents discover a desolate amusement park, and as the sun sets, food magically appears in the dusty restaurants. Chihiro instinctively knows something is wrong, but her parents ignore the warnings and gorge themselves on the exotic food. The little girl wanders off and finds a boy, Haku, who tells her to flee before the sun has completely set. When Chihiro returns to her parents, she discovers she’s too late – they’ve transformed into pigs, and she’s now trapped in a world of shuffling spirits.

The rest of SPIRITED AWAY is a gorgeous, wondrous, awe-inducing hero(ine)’s quest, as Chihiro learns how to survive in this realm of gods and spirits. Some of it’s whimsical, some of it’s genuinely violent (a dragon’s fight with enchanted paper airplanes is as bloody as any PG-13 live-action thriller), but it never stops feeling as if Miyazaki has opened a doorway into some universal subconscious. That’s a remarkable thing to say, considering that the film is also steeped in Japanese symbolism and mythology (the amusement park turns out to be a resort for “eight million gods”). But the layers don’t end there, because Miyazaki also works in his usual themes of nature vs. industrialization (one of the visitors to the resort is a river god who has been turned into a sludge monster as a result of tons of dumped rubbish), the value of work (by taking a job at the resort to survive, Chihiro turns from a sullen child to an assured young adult), the liberation of flight, and the place of girls in society (nearly all of Miyazaki’s films feature youthful female protagonists).

When I saw Miyazaki at that press conference, someone asked him what he was proudest of in SPIRITED AWAY, and his answer was astonishing: “I am proudest of the fact that this film ends with a little girl on a train.” Technically that’s not completely accurate – SPIRITED AWAY runs for another 15 minutes or so after Chihiro’s train ride from the resort out to see a distant sorceress who she hopes will save her friend Haku. But Chihiro’s character has completed her arc as soon as she gets on the train – she has chosen to make the unknown trek for Haku over either her own safety or her parents’, who are in danger of being eaten soon – and the train ride through lonely, twilight realms, feels like an epiphany. Even though Chihiro must still confront a sorceress and solve a riddle to save her parents, those scenes are wrapped up quickly. SPIRITED AWAY really is over already.

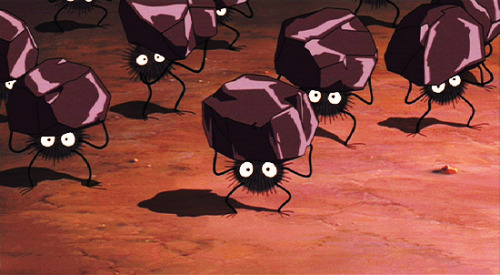

However, one film in Miyazaki’s canon is even more unconventional than SPIRITED AWAY in terms of how it dispenses with the usual rules of storytelling, and it’s Miyazaki’s other masterpiece: MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO. Here’s what is most stunning about TOTORO: Absolutely nothing happens in it…and it’s impossibly compelling. Really – there’s no real plot, no villain whatsoever, no ticking clock, no b-storyline, no big action scenes. The story (such as it is) follows a father who has moved his two young girls to the country while they wait for their mother to convalesce from a serious illness. In the old country house, they first encounter small dust spirits, but the girls soon meet Totoro, a huge spirit of the surrounding forest who looks like a cross between a cat, a teddy bear, and a squirrel. Totoro takes them for rides in Catbus, a vehicle that resembles Alice’s Cheshire Cat and roams the countryside at night on multiple legs.

And that’s it. Well, there’s a dramatic climax when the youngest child, Mei, runs away in fear that her mother will never recover, but that’s the closest TOTORO comes to a plot point.

But it hardly matters, because TOTORO is one of the most genuinely magical, delightful films ever made. It’s about how we commune with nature when young, and how we can retain that sense of wonder. It’s also breathtakingly beautiful; the backgrounds are all suitable for framing, exquisitely painted scenes of trees and fields and deep, dark forests.

No discussion of Miyazaki would be complete without mentioning his musical collaborator, Joe Hisaishi. It’s interesting how often great directors are made greater by a partnership with a great composer – think Hitchcock and Herrmann, or Lynch and Badalamenti. It’s impossible to imagine NAUSICAA without that throbbing electronic music, or HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE sans the full orchestral waltz-inspired theme. Hisaishi provides the ears to Miyazaki’s eyes…and heart.

In the interest of focusing mostly on what I consider to be Miyazaki’s two best films, I’m ignoring others that I’d probably consider equally as fine while viewing them. PORCO ROSSO, about a World War I aviator who has chosen to live as a pig, apart from humans (yes, Miyazaki has a pig thing), and PRINCESS MONONOKE, which features a dying protagonist and a feral wolf girl, are his two most adult works; KIKI’S DELIVERY SERVICE is about a teenaged witch forced to live alone at 13, and features one of cinema’s great cats (her familiar, Jiji);

LAPUTA – CASTLE IN THE SKY is Miyazaki’s most steampunk film, with a sky full of brass-plated flying machines and floating cities; and his last film, PONYO, includes images that have haunted me since I saw them (specifically, two children sailing a toy boat over a flooded forest while massive, armored, Devonian-era creatures swim just beneath them). The latter film, by the way, also demonstrates Miyazaki’s skill in dismissing stereotype when it comes to endings: The title character, the fish who has become a human girl, has unleashed magic that could destroy the world unless her friend Sosuke can save her…which he does by assuring her goddess mother that he will love her no matter what form she’s in. Miyazaki has brilliantly defied expectations (a battle between sea gods and magicians!) to offer instead a lovely message about tolerance.

If you haven’t really delved deeply into Miyazaki yet, the good news is that Disney has released most of his films on DVDs now, with both subtitles and dubs. Most of the dubbing is quite good (especially SPIRITED AWAY, in which the vocal performance of Suzanne Pleshette as the witch Yubaba may even surpass that of the original Japanese actress), but some of the English-language performances really strike discordant notes. If you can handle subtitles, go for it; you’ll almost always get the better performances, and you’ll know they’re exactly what The Man himself had in mind.

In lieu of just the usual link to a trailer (and because I’m guessing most of you have already seen these trailers anyways), here’s a little surprise treat: Joe Hisaishi (on piano) performs the theme from TOTORO with a nine-piece string section, and obviously has a ball doing it:

And here’s a nice two-part interview with Miyazaki:

--Lisa Morton