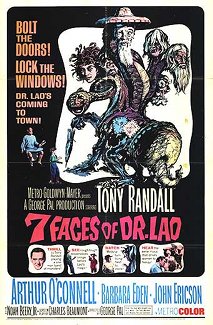

"7 Faces of Dr. Lao" (1964)

I read the novel The Circus of Dr. Lao a good fifteen years or so ago. Right now, I’m really wishing I hadn’t. After sitting through the film adaptation, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, I can see it was a beautifully crafted movie, amazingly well made for its time, but with the spirit of the novel still in my mind, I’m having a difficult time accepting it.

7 Faces of Dr. Lao is set in a small western town probably around the turn of the century. It is inhabited by all sorts of archetypes—the lying tycoon, the idealistic journalist, the strong yet guarded widow, drunks, layabouts, the vain and the bitter. In the midst of the town trying to decide whether to sell out to the tycoon, a mysterious Chinese man arrives and sets up a circus. The attractions reveal secret truths to the townspeople, sometimes truer than they ever wanted to know. However, with the revealing of these truths the townsfolk learn their inner strength and the town is saved, the widow melts in her iciness, she and the idealistic journalist fall in love and all is well with the world.

There are extraordinary things in this movie. The main one is the performance of Tony Randal as Dr. Lao and his many faces (he transformed into every attraction in his circus, from the serpent to the god Pan) and can go from whimsical to sinister and be completely believable anywhere in between. The director was George Pal, famous for his stop-motion Puppetoons and for being the mentor to Ray Harryhausen. His special effects were groundbreaking for 1964. And there was a well-written, fantastically paced screenplay by one of my favorites, Charles Beaumont (known to most for his “Twilight Zone” scripts). All in all, it was a very well-made movie.

However, it was a crappy adaptation. The thing I remember most about the novel, and what I adored the most, was its quietly sad tone, the sense of having once had hope in the human race but, after witnessing too much pettiness and vanity, having given up and seeing mostly the dark side. The movie had a whimsy often found in Ray Bradbury stories; a sense of wonder through a young boy’s eyes and, although the darkness is there, the light will eventually win out. While watching 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, it occurred to me that the movie adaptation of Something Wicked This Way Comes was more loyal to the spirit of the Dr. Lao novel than its own adaptation. On an odd trivia note, not only were Bradbury and Beaumont close friends but Something Wicked was being written at the same time this movie was being made.

I can whole heartedly recommend 7 Faces of Dr. Lao because it truly is a great, well made movie. But if you go into it expecting the novel, you will be disappointed. If you look at it as its own, separate story, I think you’ll be able to dig it a whole lot more.

--Jen

BOOK:

"THE CIRCUS OF DR. LAO" by Charles G. Finney (1935)

Originally published in 1935, this short novel has withstood the test of time very admirably. Its longevity is likely due to the subject matter: people, and the reasons to dislike or dismiss them. Bitter rather than curmudgeonly, the text offers little to recommend man as a species or the denizens of Abalone, Arizona in particular.

The story is told in the style of a classical fantasy but with a contemporary setting. Into the small town comes Dr. Lao; he first has advertisements for his circus printed and distributed, then leads a small parade through the town. The parade is short, only a handful of carts, but the contents are magnificent: a unicorn, a chimera, a sea serpent, a werewolf, the golden ass of literary legend and a millenia-old magician privy to the secrets of life and death, among others. The majority of the participants are animals, but animals hitherto reserved for fantasy and imagination.

Immediately the reader is granted insight into the minds of the townsfolk. Fancying themselves sophisticated, they denounce the tiniest of imperfections in the wondrous creatures. Imagining themselves wise, they refuse to accept the existence of such creatures even when confronted by them. Those who do not put on airs are shown to be no better: rather than be amazed by the majestic beings they're encountering, they complain about the lack of elephants and other commonplace staples of circuses.

The circus sets their meager three tents and the citizenry visit. At the exhibits they meet their foils, skewed mirror images of themselves which lure them into revealing their true natures. There is no inherent malice, however, no attempt at corruption, merely chances - rarely taken - for people to exhibit their noblest sides. In the end, Dr. Lao provides a demonstration from an ancient culture which shows how that group of people freed their baser impulses and suffered for it; in so doing he holds the entire town up to the same sort of altered reflection.

At the end of the book is a summary. The author indulges his senses of sarcasm and humor while also providing hints as to the eventual outcomes for many of the characters in the novel.

A strong book, a strange one, and a wonderfully subtle one.

Five stars out of five.

--Bill